What If Professional Learning Was Like Playing a Game?

Posted on

You are part of a teacher leadership team that just led a successful professional learning session on best practices for teaching science. Now you’re charged with organizing a study group to design, implement, and test inquiry-based science lessons. With room for just six teachers, which one do you choose for the last spot — Maria, who is concerned that an inquiry approach might mean her students miss out on content? Or Jada, an experienced educator who always has fun activities for students but doesn’t always cover the most important ideas?

That’s the type of scenario that might arise when playing Leading Professional Learning, a simulation game that provides a unique means for school leaders to learn about shaping professional learning to best meet the needs of their faculty members.

“The game opens your eyes to the wide variety of professional learning opportunities for teachers,” says Peggy Willcuts, a senior STEM education consultant at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory in Richland, Washington, and an early user of the game. “It is this giant box of possibilities.”

Game-based learning is growing as a way for teachers to engage students in solving problems, and schools are teaching game design to prepare learners for today’s growing industries. But rarely have educators had the same kinds of opportunities to incorporate game-based learning into their own professional growth. Leading Professional Learning seeks to change that, conveying research-based principles in the context of playing a collaborative board game.

Bringing it to life

Developed and published by WestEd, the game provides an interactive experience focused on the critical decisions that go into designing and implementing professional learning initiatives aimed at generating sustainable improvements in teachers’ practice. The game is based on Designing Professional Development for Teachers of Science and Mathematics, a widely read, research-based guide by Katherine Stiles (a codeveloper of the game), Susan Loucks-Horsley, Susan Mundry (another codeveloper), Nancy Love, and Peter Hewson.

“A book is one thing, but we really wanted to bring it to life,” says Stiles, a WestEd Senior Program Associate. “The people playing the game are a team. They really have to work together to think about the moves they are going to make, and why, then they can apply what they learn to their real-life planning of professional learning for teachers.”

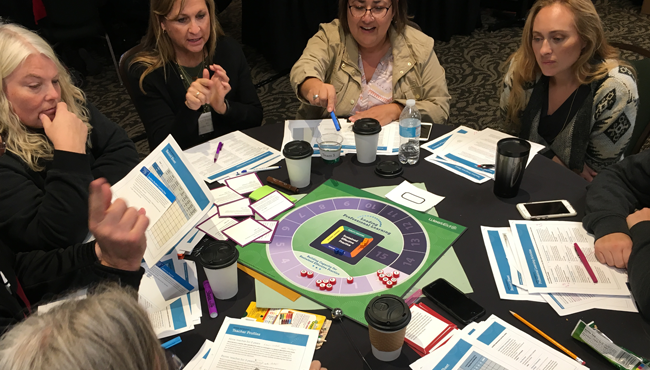

Leading Professional Learning includes materials for up to four teams, each with three to five people, and is designed to be accompanied with in-depth facilitated discussions throughout the game to support reflection on what the participants are learning. The game introduces challenges and decision points that participants will face when planning a professional learning system and implementing plans for sustained, long-term professional learning in their own settings. Stiles says the game is grounded in research-based principles for effective professional learning, the change process and adoption of innovations, and data-based decision-making, and that it is meant to provide “a process for learning about professional systems as well as a catalyst for extending leaders’ knowledge about and ability to lead change in their own schools and districts.” Facilitators who work with participants regularly continue to connect lessons learned from the game to supporting participants afterward as they design and implement their own professional learning systems.

Toward sustained effective practice

“What happens in the game is similar to what happens in real life,” Willcuts says. A team might learn they don’t have a large enough budget for what they want to do, or they neglected to consult the principal before moving forward, or they’ve received a discouraging evaluation. Willcuts says participants benefit from the game’s challenges and what she describes as “best practices” that emerge as players work to advance all their teachers to the ultimate goal of “sustained effective practice” at the board’s center.

“I absolutely love the format, particularly the way we had to track our decisions and the feedback we received from our ‘monitor,’ the person in the game providing the results to us after each decision,” says Robin Oldfather, an elementary special education coordinator for the Plano Independent School District in Texas. She played the game at a Learning Forward conference in Orlando in December 2017. “I walked away with a far greater appreciation for the importance of reflection, the need to present the research base first, and the realization that I might be too quick to move forward at times.”

The immediate feedback as the game is played, along with having an “in-depth, expertly facilitated debrief” following the game, allows participants to consider how they might translate the professional learning strategies into their own work in their districts, says Stiles.

“What stood out for me is that the game almost immediately required teamwork and a sense of common purpose among the players.”

According to Heather Sisson, an elementary science instructional coach with North Thurston Public Schools (Washington), “What stood out for me is that the game almost immediately required teamwork and a sense of common purpose among the players.” Formerly a literacy coach, she regularly provides professional learning in a variety of settings, including working with teachers from multiple grade levels, leading school-based and districtwide sessions, and facilitating professional learning communities. She adds that the participants she has played the game with comment on how much they’re able to recall of what they’ve learned from the experience. “That often isn’t the case from lecture-type delivery, most curriculum trainings, or even webinars. I strive to make my professional learning sessions as interactive and collaborative as this game.”

In October 2017 in Washington, Willcuts facilitated the game for more than 200 teacher leaders who had already been leading (or were viewed as having the potential to lead) science professional learning for their peers in their districts. She has also facilitated the game several times with smaller groups, including school and district leadership teams, and says the game provides critical learning opportunities for anyone who is responsible for funding professional learning initiatives.

Stiles has used the game with University of Indianapolis students pursuing graduate degrees in Education Leadership and principal licenses. She says the aspiring school leaders walk away with the lesson that successful professional learning is grounded in content, and that the most effective professional learning designs are the ones that specifically address teachers’ and students’ learning needs.

Learning in a “risk-free environment”

In Leading Professional Learning, teams focus on improving science teaching and learning, but the game’s principles are applicable to implementing professional learning for any subject area and any grade level, kindergarten through college, according to Stiles. She says educators from a range of content areas, such as mathematics and English language arts, who have experienced the game have been able to easily translate its “big ideas” into their own content areas. Stiles further says that when teams include educators from different content areas, playing the game gives them opportunities to discuss designing professional learning plans across different subjects.

For any participants, a central lesson of the game is that it’s important to have a good sense of the teachers for whom professional learning is being designed. That’s why the game provides detailed descriptions of the teachers in the hypothetical school. The descriptions specify each fictional educator’s years of experience and explain their particular strengths and preferences, such as Jada’s talent for fun activities and Maria’s concern about inquiry-based approaches.

The game’s fictional educators include a mix of veterans and new teachers, some already taking leadership positions, some unsure about trying new things, and, of course, those who are dismissive toward school improvement efforts in general. While the game may give any educator a glimpse into the complexity of planning and delivering professional learning, Willcuts says it can be especially beneficial for those who already have some experience with delivering professional learning and might be looking to try different approaches: “For those ready for something new, the game is powerful.”

Oldfather attended the Learning Forward conference with other members of her district’s Professional Learning Commission, but because each member works on different aspects of professional learning, they went separate ways during the conference. Oldfather says she chose the session featuring the game because she was intrigued that a simulation could teach her how to build capacity for sustaining effective teaching practices.

“I was surprised at the deep learning I gained as I experienced the simulation with complete strangers,” she says, adding that she definitely wants to use the game with members of her own district’s team. “The largest benefit to me was being able to try various scenarios and fail in a risk-free environment. This learning could shave months and years off the time it usually takes to reach success with professional learning initiatives.”